Setting the Scene

The International Space Station (ISS) is the closest humanity has come to building an embassy in low Earth orbit. Launched in 1998 and continually inhabited since 2000, the ISS is a modular complex weighing around 420 tons and spanning the length of a football field. It circles the planet every 90 minutes at roughly 28,000 km/h—a speed at which both coffee and diplomacy require a steady hand.

A joint venture between the United States (NASA), Russia (Roscosmos), Europe (ESA), Japan (JAXA), and Canada (CSA), the ISS was conceived during the late 20th-century thaw, as a kind of post-Cold-War handshake. The intention was to do science together, share costs, and keep high-profile astronauts from sitting idle. It has succeeded in all three—though sometimes more in spite of geopolitics than because of them.

Microgravity, incidentally, is why breakfast cereal floats. It’s also why most ISS science involves watching ordinary objects behave in faintly absurd ways, and why all food is served in packets that require scissors and a certain stoicism.

Political Theatre at Apogee

While the ISS was designed as a model of international cooperation, its day-to-day running is not immune to terrestrial rivalry. Each agency controls its own modules and time slots for experiments; even access to shared laptops and communication channels is partitioned more by treaty than by convenience.

- Hatch Etiquette: The arrival of a new crew is always a photo opportunity, but also a logistical negotiation. National segments are managed independently; crossing from the US to Russian side is routine, but occasionally tense, depending on what’s happening several hundred kilometers below.

- Experiment Scheduling: Research is scheduled in advance, with time allotted by contribution and, unofficially, by diplomatic leverage. During periods of tension, some experiments are quietly rescheduled or delayed. Occasionally, the dispute is about something as mundane as which side gets the video feed for a national holiday.

- Culture and Playlists: The shared US/Russian laptop, a relic of early 2000s procurement, is regularly loaded with both Russian pop and Western rock. It is an open secret that, in the early days, the only genre guaranteed not to offend anyone was ABBA. Since then, silence has sometimes proven even safer [8].

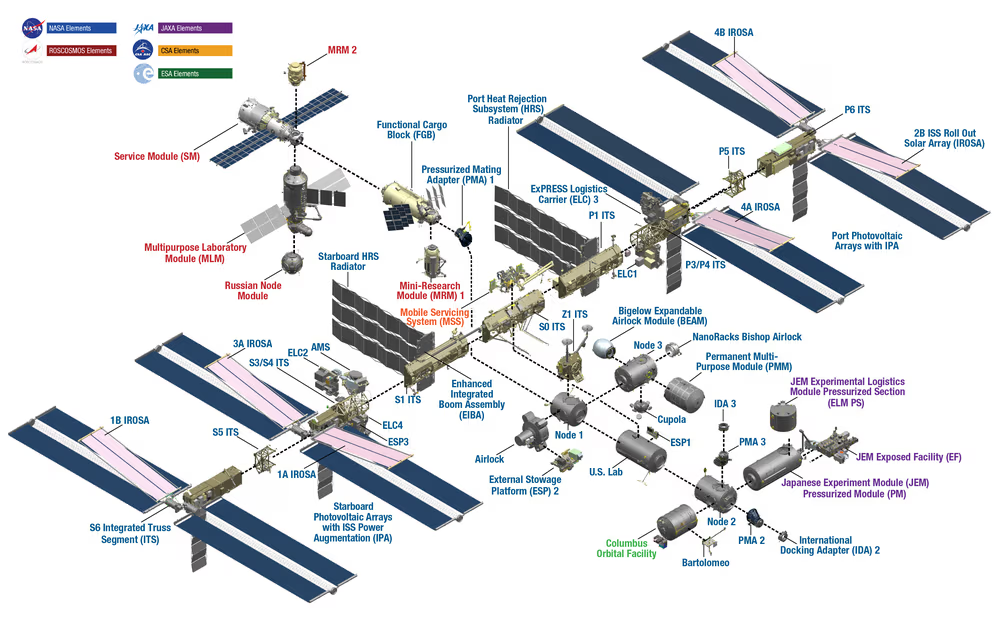

Drawing of ISS with who owns which parts.

Drawing of ISS with who owns which parts.

Flashpoints in Orbit

Crimea and the “Cold-Vacuum Stare”

After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, NASA received instructions to suspend contact with Russian government representatives, with the ISS as the only exception [1]. Cooperation continued, but in an atmosphere more frosty than collaborative, with joint activities pared down to only those essential for crew safety. Statements from both agencies insisted “space cooperation rises above politics,” while privately, teams described an era of formal politeness and minimal improvisation.

The Nauka Module Incident

In July 2021, Russia’s Nauka science module docked to the ISS. Minutes later, its thrusters unexpectedly fired, rotating the station by more than 500 degrees and prompting NASA to declare a spacecraft emergency [2]. Operations teams on both sides worked together to regain control, and the incident was described publicly as a technical anomaly. In private, there was relief that the outcome was merely unsettling, rather than catastrophic.

2022–25: Sanctions and Shifting Timetables

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine led to a new era of uncertainty for the ISS partnership. Roscosmos leadership variously announced an intent to leave the station “after 2024,” then later hinted at remaining until at least 2028 [3]. For their part, NASA and partners accelerated planning for alternative stations and contingency operations [4]. In reality, both sides appear determined to avoid being blamed for an abrupt end to ISS operations—a diplomatic standoff playing out in orbital schedules and joint press briefings.

Remarkably, daily life in orbit has changed little. The cleaning rota for the zero-gravity toilet is perhaps the single most stable institution aboard, immune even to sanctions (footnote: reportedly, not even the most experienced astronauts volunteer for this duty twice).

Humans Versus Hardware

What’s striking about the ISS experience is the contrast between political tension on the ground and camaraderie among crew in orbit. Astronauts from all agencies routinely train together, share meals, and collaborate on everything from scientific research to minor engineering improvisations. Several astronauts, when interviewed after long-duration missions, have noted that relationships in orbit are often more functional and straightforward than those among their own management teams on the ground.

This is not to say friction doesn’t exist; it does, but is generally resolved by negotiation and the shared understanding that, in orbit, everyone is equally dependent on everyone else’s competence and goodwill.

Money, Prestige, and Exit Strategies

Operating the ISS costs NASA about $3 billion per year, with other partners contributing in proportion to their modules, launches, and experiments [5]. There is an annual ritual in Washington and Moscow in which the future of the ISS is debated in budget hearings and agency press conferences. These discussions generally result in announcements that cooperation will continue “for the foreseeable future,” a phrase that here means “until another meeting is scheduled.”

China, excluded from the ISS partnership for political reasons since 2011, has built its own space station, Tiangong [6]. This is both a demonstration of technical independence and an implicit commentary on the limits of internationalism in orbit.

As for what happens to the ISS after 2030, current plans call for deorbiting the station over the South Pacific. There is, inevitably, a polite dispute over which agency gets to keep the ceremonial “last key”—a matter unresolved as of this writing.

The eleven Expedition 68 crew members aboard the International Space Station pose for a portrait. In the front row from left, are cosmonauts Anna Kikina, Sergey Prokopyev, and Dmitri Petelin. In the next row, are astronauts Samantha Cristoforetti of ESA (European Space Agency) and Koichi Wakata of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). In the back, are NASA astronauts Jessica Watkins, Kjell Lindgren, Bob Hines, Frank Rubio, Josh Cassada, and Nicole Mann. A symbolic key, representing the traditional change of command ceremony, that Cristoforetti earlier handed over to Prokopyev floats in the center of the frame as he begins his spaceflight as Expedition 68 Commander.NASA

The eleven Expedition 68 crew members aboard the International Space Station pose for a portrait. In the front row from left, are cosmonauts Anna Kikina, Sergey Prokopyev, and Dmitri Petelin. In the next row, are astronauts Samantha Cristoforetti of ESA (European Space Agency) and Koichi Wakata of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). In the back, are NASA astronauts Jessica Watkins, Kjell Lindgren, Bob Hines, Frank Rubio, Josh Cassada, and Nicole Mann. A symbolic key, representing the traditional change of command ceremony, that Cristoforetti earlier handed over to Prokopyev floats in the center of the frame as he begins his spaceflight as Expedition 68 Commander.NASA

Elon Musk’s Perspective

No account of ISS politics is complete without mention of Elon Musk and SpaceX. Since 2020, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has replaced Soyuz as the main US access to the ISS. Musk has, on several occasions, offered to keep the ISS operational should Russia depart—sometimes as a public statement, sometimes as a tweet, sometimes as both [7]. NASA is now reliant on commercial operators for both crew and cargo transport, a dynamic that has shifted the balance of negotiation.

SpaceX’s operational style—“move fast and break things, but preferably not the station”—is seen as both an asset and a risk. Astronauts appreciate the company’s engineering agility, but there is a running observation (rarely made on the record) that mission updates sometimes appear on Musk’s social media before reaching official NASA channels.

Looking Ahead

As the ISS nears its planned retirement—currently forecast for “after 2030,” with the precise date left as a diplomatic cliffhanger—attention is shifting to a new generation of stations in low Earth orbit. Private ventures such as Axiom Space, Northrop Grumman, and Blue Origin are developing commercial platforms that promise upgraded habitats, flexible laboratory space, and more “customer-centric” service contracts. NASA and its partners are betting that competition, rather than cooperation-by-treaty, will sustain human presence in orbit.

Whether this market-driven approach will reduce geopolitical tension is uncertain. Negotiations over crew slots, experiment scheduling, and, inevitably, cleaning duties will move from memoranda of understanding to contractual fine print. What once required multilateral negotiation now hinges on payment terms, service-level agreements, and—perhaps—the relative diplomatic skills of procurement officers.

The fate of the “last key” to the ISS remains unresolved, but its symbolism is relevant far beyond low Earth orbit. As humanity contemplates permanent settlements on the Moon (via the Artemis program and international Gateway station) and Mars (currently the subject of timelines that stretch credibility as much as engineering) [4], the question of who commands, who pays, and who gets the ceremonial artifact at the end will only grow in complexity. Will the commander of a lunar base hand over a key, a tablet, or perhaps a blockchain token to their successor? Will Martian outposts develop their own rituals of closure and continuity?

The precedent set by the ISS—imperfect, improvisational, but fundamentally cooperative—will inform not just hardware standards but the unwritten rules of engagement for off-world society. As in low Earth orbit, human nature and national ambition will shape the politics of airlocks and authority, long after treaties are signed.

The orbital forecast: a proliferation of stations, private and public, with politics shifting from nations to consortiums and corporations. On the Moon and Mars, a fresh set of stakeholders will discover that, whatever the architecture, it’s still a human institution—right down to the last key, and whoever volunteers to scrub the first lunar toilet.

References

NASA suspends most contacts with Russia (ISS excepted):

Ban on Russian contacts spreads to space agency NASA – Reuters, 2014.

Details NASA’s 2014 decision to suspend contact with Russian officials following Crimea, except where ISS operations were concerned.Nauka module misfire and ISS attitude loss:

Russian lab module knocked International Space Station out of position – Space.com, 2021.

Explains the July 2021 incident where Russia’s Nauka module caused a temporary loss of ISS attitude control.Russia delays ISS withdrawal to at least 2028:

Russia tells NASA it will stay with International Space Station until at least 2028 – Reuters, 2022.

Covers the shifting position of Roscosmos on ISS withdrawal timelines.NASA’s Lunar Gateway as successor program:

Gateway: NASA’s home base for Artemis lunar exploration – NASA, 2024.

Official site outlining NASA’s Gateway project, the ISS successor in cis-lunar space.ISS operating cost and budget review (GAO):

NASA’s Management of the International Space Station and Efforts to Commercialize Low Earth Orbit – NASA Office of Inspector General, 2021.

A detailed audit of ISS costs and NASA’s commercial transition strategy.China’s Tiangong station and ISS exclusion:

Tiangong space station – Wikipedia, 2025.

Provides context on China’s independent space station and its exclusion from the ISS program.Elon Musk offers to support ISS operations:

Elon Musk Offers to Help NASA Keep ISS Flying Amid Russia Tensions – Newsweek, 2022.

Describes Elon Musk’s response to geopolitical tensions affecting ISS collaboration.Music in space: NASA's official list of ISS wake-up songs:

Chronology of Wakeup Calls – NASA, 2023.

Documented history of songs played to astronauts aboard the ISS, reflecting informal culture in orbit.

Orbital Forecast

The next decade will see new players, new stations, and familiar disputes in new forms. The ISS may finally retire, but politics—like orbital debris—remains a persistent feature of low Earth orbit. As for the last word: “In space, as on Earth, everyone eventually negotiates for air.”